Against the backdrop of Persian art and craft of carpet weaving, wrapped in seven sheer layers of Persian folkloric-mystical tales, Anita Amirrezvani weaves her narrative of The Blood of Flowers, her first novel.

The story’s unnamed narrator tells her life story, woven delicately among the colorful flowers and leaves and birds and animals which gradually appear as five carpets are woven. The seven tales, alluding to the seven mystic steps Sufi masters have set to lead seekers of absolute truth or love to the most inner self, serves a two-fold function: to help the narrator demystify the ambiguities of her own fate and destiny and to encourage her to bear it courageously and to keep the reader from losing patience while confronting the extremities of pains and hopelessness woven into the fabric of the narrator’s life.

The art of carpet weaving is not used decoratively, informatively, or even metaphorically, as has been suggested by some reviewers. Indeed it plays a structural as well as an instrumental role in her story, functioning just as the art of illustration and miniature did in Orhan Pamuk’s celebrated novel My Name Is Red.

Anita Amirrezvani successfully, with a fairy tale style narrative, tells us a magical tale which unfolds in a magical land and a magical time. Though the setting is too far away in Isfahan and in the seventeenth century, the carpet design lends its lack of perspective to the characters in this tale, allowing them to transcend time and space to connect to us, the reader, here and now. However this universality never diminishes the liveliness, vividness and individuality of the characters, thanks to our author’s skillfulness.

The story’s narrator is a carpet weaving villager who is caught in a web of misfortunes but manages against all odds to pull herself up into the centre of a male-dominated carpet industry as a major designer. In a charming and engaging, though very sad, story we follow her obsessively from the profound depth of her misery to the peak of her glory as if it is our own fate. Exaggerated as it appears, the story is an idealized narrative of an intense infusion of centuries of epical struggles of Iranian women to overcome the obstacles of male-dominated tradition, religion, and politics which hinders them. (I very deliberately and consciously avoid the term culture when the suppression of women is concerned. I very strongly feel that Iranian “culture” is not misogynistic and it seems, judging from the two male characters in the story, that the narrative’s father and her uncle, Amirrezvani agree with me.)

The sharp contrast between the wealthy and haughty and the poor and humble, the glory of the city of Isfahan with all its magnificent bridges, mosques, palaces, and public squares and the extreme poverty, disease, filth and squalor of the narrator’s life, are effective in giving the idealized characters a vivid life, just as the play of colors separate the various idealized layers of images in the carpet designs. The dichotomy of two worlds is also used to advance various themes in the novel as well, such as sexuality, child bearing, marital discrimination, and luck and chance versus merit.

Our narrator’s divided city, with all it contrasts, is a natural setting to tell us that once upon a time “chance and luck” overrode merit; women’s life was glued to only one tiny thread, the child or the children she bore; the only value in a woman was in the pleasure she could bestow; at the age of thirty she was considered old; her dowry was the price she had to pay to buy a life; the world was divided into two halves, those who lived it and those who stare at those who lived it; some did not even have the right to a lawful marriage; others were destined to a term marriage for a limited time only, sigheh; and the institution of family was the prize not for all but for a privileged few.

Our narrator’s divided city is a two-colored life, and our narrator is a denizen of the dark and unfortunate side. Her struggle is not only to achieve happiness, in spite of what was destined for her and many other women throughout the centuries, but an effort to redefine “happiness.” The narrator, to her own disbelief, succeeds in bringing a new life and a new meaning to a concept which for centuries was imprisoned in rigid cliché.

“I had never imagined that a woman like myself, alone, childless, impoverish—could consider herself blessed. Mine was not a happy fate, with the husband and seven beautiful sons, that my mother’s tale had foretold. Yet with the aroma of the pomegranate-walnut chicken around me, the sound of laughter from the other knotters in my ears, and the beauty of the rugs on the loom filling my eyes, the joy I felt was as wide as the desert we had traversed to reach our new life in Isfahan.”

Not only has the narrator crossed a line to change the definition of happiness, but she dares to see the boredom and unhappiness in a life that for centuries was considers ideal and desirable. When she crosses that border and reaches the land of her dreams, she finds just sadness, waste, and loneliness—nothing but a gilded prison. She considers herself lucky not to dwell in that realm. She finds that in reality it is the habitants of that life who are deprived, since they cannot make a mistake and learn from it, since they live an unworthy, unexamined life which is nothing but a gradual death.

“I did not envy her. Each time a gate closed with a thud, I was reminded that while I was free to come and go, she could not leave without an approved reason and a large entourage, she could not walk across the Thirty-three Arches Bridge and admire the view, or get soaked to the skin on a rainy night. She could not make the mistakes I had and try again. She was doomed to luxuriate in the most immaculate of prisons.”

There is a myth in carpet weaving circles that the carpet weavers intentionally leave at least one erroneous knot in the carpet as a sign of humility and submissiveness to God, since it is only He Who is perfect and can create perfection, while some experts in Iranian medieval arts hold that there is no such thing as an intentional error in art and that this myth is just a clever justification for the unavoidable. After all, a work of art as massive as a carpet with such a complexity of design is never devoid of mishap.

Following the carpet weavers’ myth, Amirrezvani, intentional or otherwise, leaves some missing knots in her tapestry. I found it troubling that it ends so rapidly and so “heavily” in a very uncustomary way. The long paragraph running from page 359 to 360, just eight pages to the end of the story, is a much-delayed explanation of the narrator’s “trade of life of occasional opulence” for the life of “hard work.” One needs to know this when the narrator makes the decision or at least shortly thereafter. The sophisticated explanation, attributed to her learning from her uncle, with all the mystical tone in it, obviously justifies the expectation. As she gains in knowledge gradually and step by step, as she strengthen her self-confidence through her experience and her learning, and since she distances herself from her sigheh, physically, mentally as well as metaphorically, she waits too long to talk about it, and that only too little.

The other missing knot, which I’m impatient to air my feminist’s view of, is the letter that the narrator writes to her friend Naheed expressing her regret for not “doing her best to stop her renewal of her sigheh,” which had been decided upon by her relatives even prior to her knowledge of Naheed’s engagement. I wonder why she did not ask Naheed what she would have done had she known about her sigheh. Would she have broken off her engagement and consequently her marriage? Would it have been for her sake? Or for finding Ferydoon, (her temporary husband and now Naheed’s permanent husband), no longer worthy of herself ? Indeed, this short letter deserves good amount of consideration from a feminist perspective. There is a solid tone of inferiority embedded in the narrator’s guilt and consequently her asking for forgiveness. I wondered why she felt so obliged to her friend and not the other way around.

However, neither of these two objections diminishes the joy of reading such a well-crafted tale. Indeed, I expect the book to stir much discussion both in Iranian literary circles as well as among feminists on these two issues, as well as many others, particularly over the aesthetic aspect of story. Amirrezvani may have philosophical and aesthetic views on both objections. She may believe that more time was needed for the narrator to achieve a status on par with Naheed’s, or even some moral consideration which is left unclear in the story. I’m looking forward to hear her comments on these issues.

One last point. This book may be of interest for art historians for many reasons just as My Name Is Red was read and used widely by those interested in all aspects of the Iranian and Ottoman miniature and illustrations. While a little knowledge of Iranian medieval art would help the reader, particularly non-Iranians, enjoy the book more, I very much hope the book itself would encourage the reader to learn more about our magnificent heritage. A few years ago at NYU, Orhan Pamuk gave a talk, and an Iranian in the audience exclaimed to a friend of mine, “What if we had a writer like him!” I hope this audience member discovers Amirrezvani; she might be the writer she was looking for.

I extend my warmest thanks to Ms. Amirrezvani for her massive work, which is truly the labor of love.

PS: The author's publicist has kindly offered to give free copies of the book to the first five readers of Iran Writes to ask for them. Don't be shy!

5 comments:

Hello, I was wondering if I can get one of those free copies.

Hi mina, I have been waiting for a new post for while. You write about the book so beautifully. I would love to read the Blood of Flowers. I was wondering if I could have a copy.

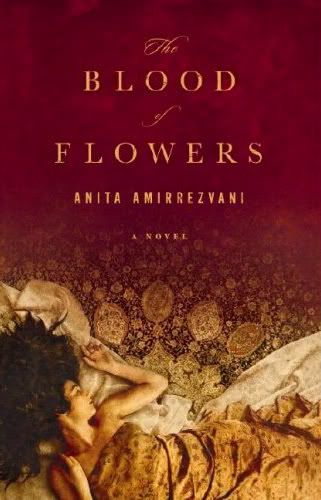

I just finished this book and I loved it! It was something I picked up from the bookstore because I loved the cover (I admit it lol) but I was swept up in her story and LOVED the ending.

Must be an enjoyable read The Blood of Flowers by Anita Amirrezvani. loved the way you wrote it. I find your review very genuine and orignal, this book is going in by "to read" list.

This is awesome!

Post a Comment